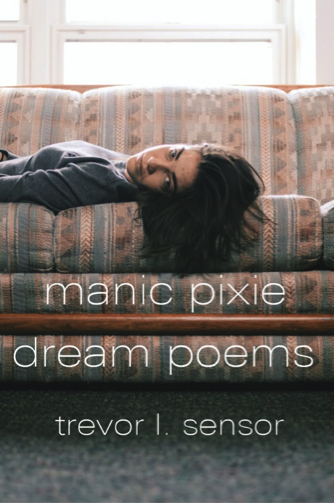

Available from independent publisher C.A. Mullins’ Bottlecap Press, the poems in Trevor L. Sensor’s chapbook sing a lamentation of unrequited love in the 21st Century. Sensor’s Manic Pixie Dream Poems, a chapbook filled with the kind of love that keeps you up at night, is dour, morose, pensive. But there is a depth in Sensor’s poems; there is reflection and contemplation, albeit of a honed-in focus on a single love: the titular Manic Pixie. Like a powerful dream no longer there, the Manic Pixie haunts the thoughts of the persona and, as such, drifts from poem to poem, filling the chapbook with her presence. But there is a beacon of hope for Sensor’s speaker because something like progress toward something like healing is, if not exactly achieved, certainly hinted at in the chapbook’s concluding pensive poems.

Available from independent publisher C.A. Mullins’ Bottlecap Press, the poems in Trevor L. Sensor’s chapbook sing a lamentation of unrequited love in the 21st Century. Sensor’s Manic Pixie Dream Poems, a chapbook filled with the kind of love that keeps you up at night, is dour, morose, pensive. But there is a depth in Sensor’s poems; there is reflection and contemplation, albeit of a honed-in focus on a single love: the titular Manic Pixie. Like a powerful dream no longer there, the Manic Pixie haunts the thoughts of the persona and, as such, drifts from poem to poem, filling the chapbook with her presence. But there is a beacon of hope for Sensor’s speaker because something like progress toward something like healing is, if not exactly achieved, certainly hinted at in the chapbook’s concluding pensive poems.

Sensor’s poems are a lament of heartbreak, of love lost and never to be regained. Manic Pixie Dream Poems is a youthful wail resulting from a somber reality check, but it also brims with passion and longing, a deep ocean of love some will never know. In this way, Sensor’s persona is lucky, though they would probably disagree. Consider these lines from “Manic Pixie Dreams”: “I screamed that you would die alone / But what I meant was / I will die alone.” The speaker suffers mental anguish from rejection, and would therefore do anything to reclaim the lost Manic Pixie for the sake of ending said mental anguish; yet, in truth, there is a deep well of emotions, of love acknowledged and passion stifled, which rises up in the expressed hopelessness of living without the beloved Manic Pixie. The reality remains, however, that she has left behind an overflowing fountain of emotions within the speaker. Sensor’s poem “Whales and Pixie Girls” explicitly draws a ghostly comparison: “the pixie girl who haunts my dreams / And pacing parking lots can’t make her go away / Nothing can make her go away.” Indeed, Sensor’s poems function like the feverish, obsessive, vexing thoughts of lonely, long, and loveless nights.

By the latter half of the chapbook, there seems to be a slight shift toward recovery, though Sensor’s persona is far from over the Manic Pixie. In “Manic Pixie Sex,” the speaker attempts to move on by having sex with another girl, but the event is overshadowed by thoughts (and actions resulting from those thoughts) of the Manic Pixie, for which the persona proclaims: “O’ how my life is such a mess.” Now then, two things to note re: Sensor’s poetic style: 1) The use of “O’” throughout the poems, which is reminiscent of older, verse-&-rhyme poetry as well as Walt Whitman’s, which, as a nod to the poetic past, was a rather nice touch throughout the chapbook; but then also: 2) The somewhat irksome lack of punctuation. Perhaps this stylistic choice was done to show that these poems are less structural and more like free-floating thoughts in the persona’s fevered mind. But an antipodal example of the beneficial and creative powers of punctuation can be found in “Manic Pixie Sex,” where commas and dashes are used with skill. Punctuation or not, Sensor’s poetic voice rings true, which fortifies and strengthens each poem.

While there may be relief for the persona at some point in the future, one thing remains clear: the speaker is going through a hectic, stormy period in life. Lovelorn and heartbroken, the persona’s extreme anguish prompts the search for a solution to life without the beloved Manic Pixie. Possible remedies include: 1) castration in the forms of both a devoted religious life and then also musings of physical purges; 2) a near-Freudian desire to return to infancy and childhood; and 3) considerations of attempting to be with someone else; however, none of these possible remedies quench the speaker’s burning flames of love for the Manic Pixie. Thus her ever-present specter haunts the speaker both in dreams and during sleepless nights, shrouded in hazy layers like a whale swimming through the ocean’s depths. But “The Wolf” shows this to be a systemic problem: the speaker experiences anxiety and fear from interaction with other girls too. See, for example, “Manic Pixie Sex” again, wherein intercourse with some other girl is not enough to make the persona have a ‘good time’ and stop thinking about his beloved. In mentioning having sex with other girls, the speaker shows attempts at moving on, but each instance is accompanied by anxiety and disappointment.

The chapbook’s concluding two poems provide insight into the fate of the poems’ speaker. The abrupt ending of “Manic Dreams in Iowa” suggests the persona might have a chance at recovery. On a deeper level than in the preceding poems, the speaker has come to grips with the fact that the Manic Pixie will not return, but nevertheless hangs on—until, that is, someone else is found to love. This is threat-like and bitter, but a hard nugget of truth: a revelation. The Manic Pixie will stay on his mind until all he has left to love is meager and small, at which point he will be forced to look elsewhere, settling for “table scraps / And bones for someone to love.” The final poem, “An Empty Room and Closed Doors,” witnesses the fulfillment of that bitterness, out of which springs a kind of hope. That is, if the Manic Pixie should not return (and it seems clear that she will not), then the speaker wills that all other possibilities of love be extinguished, so that there may be peace of mind to dream solely of the chapbook’s namesake.

Trevor L. Sensor’s Manic Pixie Dream Poems is a chapbook of love lost but still desired, of self-realization, of unrequited love. The chapbook’s persona reflects and obsesses on what was and what is not now until, at last, the only solution, it seems, is solitude. Sensor’s post-love chapbook, available from C.A. Mullins’ Bottlecap Press, is an emotional journey through heartbreak and sorrow, a longing for that which no longer is. From the haiku-esque “A Feat” to the really fucking good “Bruce Willis Died for Something and Maybe I Should, Too,” Sensor’s poems breathe heavily and sadly, bringing about a clear and distinct revelation: the Manic Pixie haunts eternally, such that Sensor’s speaker must try to find hope in a solitary future.

AUTHOR BIO:: dom schwab is a reader/writer of poetry/prose. dom is gay, GQ w/ no pronoun preference, a vegetarian, and lives in Chicago. dom’s most recent work has appeared in Zoomoozophone Review’s female/non-gender-conforming Issue 5, Boscombe Revolution Issue 3: Revolution & Gender, and JunkYard Kool, an anthology presented by Kool Kids Press.

AUTHOR BIO:: dom schwab is a reader/writer of poetry/prose. dom is gay, GQ w/ no pronoun preference, a vegetarian, and lives in Chicago. dom’s most recent work has appeared in Zoomoozophone Review’s female/non-gender-conforming Issue 5, Boscombe Revolution Issue 3: Revolution & Gender, and JunkYard Kool, an anthology presented by Kool Kids Press.