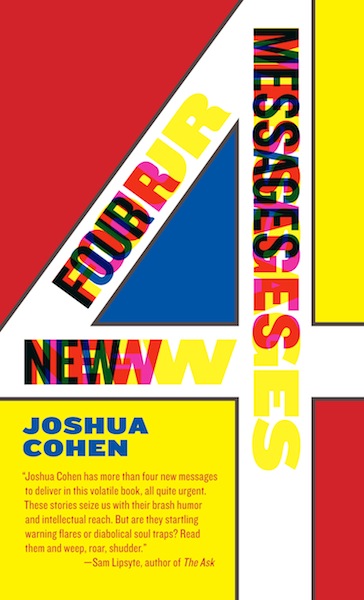

Four New Messages by Joshua Cohen

Amazon

Joshua Cohen is America’s premier young storyteller. At 32 he is the author of seven books, three novels and four story collections, with his eighth, and nonfiction debut set to release sometime next year. He’s drawn comparisons to David Foster Wallace, Thomas Pynchon, and has even been dubbed the “Jewish James Joyce.” His output, the result of legendary 12-14 hour writing days, is mind-boggling. His most recent offering, Four New Messages, put out by Graywolf Press, doesn’t, at first glance, seem to be his most ambitious, both content wise and in length, but upon deeper inspection it ranks among his finest works yet.

At just under 200 pages and containing, you guessed it, four stories, Four New Messages is compact yet sprawling, with the shortest story coming in at 30 pages long. He tackles subjects as broad as family, sex, and, most notably, disappointment (both literary and otherwise.) But it’s the net that he’s cast over these subjects that provides for an interesting premise. Using the precariousness of the internet, Cohen places his subjects within a framework that is both expansive and confining. We begin to see that the more one delves into the internet, the less options they really have, be it trying to connect emotionally to another person or losing themselves amidst all of the information, the moving parts of the web. This isn’t news, hardly, but the really compelling aspect of this collection has as much to do with how he conveys the collective isolation, frustration, and obsession as it does with the subject matter.

In “Emission” a drug dealer in Princeton is exposed by a co-ed on her blog for exposing himself. “McDonald’s” deals with a pharmaceutical copywriter trying to create something more, but can’t seem to write down a certain word that’s key to his story. “The College Borough” finds a father remembering his old writing teacher, an eccentric man exiled from New York and plopped down in the Midwest, who makes his students build a replica of the Flatiron building instead of reading his stories. “Sent” details a man traveling to an Eastern European town where all of his favorite porn actresses live.

Themes battle for supremacy in these tales as the comic meets the tragic, the ultra intelligent clash with the hyper sensitive. The lowest common denominators, our sexual urges and shared frustrations, are explored by a wide array of characters. A drug dealer with a heart, an introspective failed writer, a peculiar academic, and a man whose desires spark him to take an odyssey across the world. Here we have clichés that are warped, twisted into a new and surprisingly interesting way.

At turns funny and sad, this book also has a cautionary undertone, a warning to the majority of us who give everything over, seemingly naively so, to the internet, not quite grasping what we’re losing in the same breath.

Blog postings exposing a man for a sexual act at a party in the past, not the fact that he is a drug dealer, seem to haunt the main character in “Emission.” Google searches, the indelible imprint that strangers can make on your name, your very existence, is both a present problem, and as Cohen suggests, a weird lack of identity control that our future seems to have in store for us. The lead character, Mono is at once stuck on the outskirts of virtual reality and then, within a few hours span, encircled in its web of hearsay and innuendo. “Mono was not aware of his internet. He’d never made a habit of googling himself – it was too depressive a venture.” And in many respects he was right.

Within a week a hundredplus results all replicated his name as if each letter of it (those voluble, oragential os) were a mirror for a stranger’s snorting – reflecting everywhere the nostrils of New York, Los Angeles, Reykjavík, Seoul, as thousands cut this tale for bulk and laced with detail, tapped it into lines, and his name became a tag for abject failure, for deviant, for skank.

To pull a Monomian.

To go Monomian.

Fucking Monomial.

Tackling corporate branding and the intersection of the pervasiveness of this commercial mentality with the individual’s struggle to create something original and meaningful is examined in a beautiful, and real, way in “McDonald’s.” The narrator’s problems are those of the modern artist, and even though this ground has been toiled before it has never rung so true, or original. After an entire story about, ostensibly, a writer trying to get the gumption to put a certain corporate name into his tale, the narrator finally acquiesces.

I was tired of this, tired of inventing other worlds – “realms,” “dimensions,” I was exhausted by synonym, by quotation marks too – tired of inventing alternate worlds while misunderstanding my own, yes, yes, but also I was starving.

But upon getting to the fast food chain, the narrator loses his hunger and instead sits and observes. He ends the story with both dry humor and an acute awareness that this technological age has, in many ways, caused us to discard.

Big black and Hispanic kids drinking blackcolored and hispaniccolored sodas. Fat old white man eating burger. The woman, his wife. Mashing pills into ketchup for fries. The climatized cold. The hard silence. A silence with edges. Open carton. Flip up top. Chew pen turning tongue graveyard dark. The old man drooled above his seconds. Wife still finishing her first. Big burgers for those bloodless bodies! Those big big big big burgers! (No more writing, nothing more intelligent than that.)

Cohen continues to examine increasingly modern problems in “The College Borough.” Set against a similar backdrop of literature and art, Cohen sets his sights on highlighting, and dissecting, the differences between the urban and the countryside, relevance and non-relevance, among other things. The narrator tries to get a better feel for the mercurial professor from the big city towards the middle of the story.

As we roamed upper quad to lower, Greener became, by steps, progressively glummer until he was saying, You want to know the truth? New York’s flunked me. Why else am I here? I’ve been suspended, I’ve been expelled.

I said, You seem to be doing OK.

This is where Cohen, via Professor Greener, lays down the hammer concerning the growth of technology. It’s less theory and more meat and potatoes in the following excerpt, something that seems to fit well with the professor’s new Midwestern setting.

Not compared to how I’d be doing if publishing weren’t over, with the money gone and editors not editing, my generation’s screwed – we’re not the immigrant experience, we’re not the assimilation experience – we’re the first nothing generation, we’ve got nothing to write about and no one to read it, everyone too busy getting technologized, too harried with degrees.

The final piece, “Sent,” uses the guise of porn as a lens to zoom in on the pre- and post- communist struggles of so many isolated, nameless Eastern European towns. The question of ownership, these women losing a part of themselves the second they decide to disrobe for the camera, is placed alongside the sexual, both competing for control. Cohen argues, sometimes more subtly than others, that in the new digital age these instant, amateur pornstars lose their very identity as people around the world can now collectively gaze upon them in their most revealing moments at any time they wish. They are now out there, a commodity, no longer a person but a thing meant for consumption. The horror and honesty of this is stark. This story possesses both the best and worst of Cohen as he displays his imagination on a grand, yet human, scale at the same time he dizzies the reader in a string of densely woven ideas, sentences seemingly put down just to see how far they can go, forcing the reader to hang on for dear life, stop frequently, and re-read some of the more obscure passages looking for his hidden, deeper, meanings. But just as he seems to lose the reader, he reigns himself in, dropping sections of information that ring loudly with truth.

Our generation doesn’t have to hide anything under the bed, to secrete the forbidden in the closet, behind the shoes, behind the socks smelling like semen, the socks smelling like shoes. Instead ours is a practical pornography, with no awkward visits to newsstands or subscriptions to renew – there are no secrets, the entirety is acceptable. The computer sits proudly on the desk in plain day. There to help with the spreadsheets, with directions. We can just press a button and, naked lady.

This quote, detailing the pervasive way that the negative aspects of our growing technological state (Cohen continues the above paragraph by saying, “You come to expect that all girls take it up the pooper, take goop on their faces and into their mouths and, swallowing, that they all do so voluntarily…) gives the reader a look into a mind hard at work. Taking the often clichéd idea of pornography and raising it an intellectual level by posing deeper questions, becoming introspective and then turning the mirror on the reader himself, Cohen has blurred the line (successfully) between fiction writer and sociologist.

These messages can, at times, get lost in Cohen’s web of wordplay and almost exhaustive linguistic experimentation, but the brilliance of this collection is that it can be read for both the underlying themes, which there are plenty to dig through, and the sheer joy of a storyteller on top of his game. You can get lost in his sentences, at times sprawling and tricky, seemingly unraveling right before your eyes before he recoils it and brings it back around to his original idea. Cohen, here, is showing himself on the page, giving the reader a glimpse into what looks like an extremely polished journal, one of false starts, meanderings and, ultimately, beautiful conclusions.

I suspect that a lot of people won’t like this book. Also, something that Cohen seems to share with his predecessors Pynchon and Wallace, a good amount of people will claim they read this book when they really haven’t (see his last effort, the 800 plus page Witz for a perfect example of this.) But most of all, for those brave enough to delve in, people will enjoy this book for what it is, a meditation on the life lived through the internet, on what we gain in this digital age and, more importantly it seems, what we lose. The real enjoyment in reading Four New Messages comes right after completion when you realize that it is, in fact, for once, the journey and not the destination that matters most.

***

BIO: Patrick Trotti is the author of five digital story collections. Dozens of his short stories have been published in both print and online literary journals. His nonfiction, mostly book reviews, have appeared at jmww, Specter Magazine, and The Mad Hatters’ Review. He’s the Founder/Editor of the online literary magazine (Short) Fiction Collective and is the Co-Founder and Co-Editor of the online literary magazine THOUSAND SHADES OF GRAY. He works as an Editorial Assistant for Tiny Hardcore Press and is a reader for literary journal PANK. To find out more about his books or other work check out www.patricktrotti.tumblr.com.