In a dingy motel room in Harlingen, Texas, a seventeen-year-old girl with a mild speech impediment struggled to dislodge my erect penis from under my red gym shorts. Perched on the on the edge of a hard-backed chair, I watched her slowly work my cock loose and begin stroking it, her cheeks flushed pink with sexual desire. Detached and bored, I gazed into infinity, eyeing the chameleons darting across the greasy walls as though a complete stranger who resembled me had taken my place. Kim’s blonde friend J J intended to watch Kim service me.

Neither of them possessed a firm grasp of basic hygiene, but the cloud of Marijuana smoke sifting throughout the air masked the stifling pungency that permeated my motel room. Most of the women in Harlingen, Texas seemed to be seriously overweight, but so was I, the result of subsisting on a diet of greasy Tex-Mex food and endless bottles of ice-cold Jax beer. I had already lost my passion for Kim, and I was fairly certain that the both of them regularly slipped away to J J’s house, where they fingered and kissed each other into whatever passed for sexual bliss. I gazed off into some conceptual distance, struggling to ignore the shrieking peacocks and lowing cattle on the desiccated lawn below.

In the summer of 1982, I summarily abandoned my wife and children in southern California and fled to Harlingen, Texas, a small ranching and farming town in the lower Rio Grande Valley. Dangling at the end of my emotional rope, I was desperate to disengage myself from a marriage long-since evaporated into a grim and humorless stand-off. For over a hundred years men had shed their murky pasts and reinvented themselves by heading south, GTT, Gone to Texas, and I became one of them. A friend in San Bernardino, California had hired me over the phone to help him assemble a country band and, seeking exile, I took the gig.

So, on a stifling August night I slithered into Harlingen on a Trailways bus and stepped down into a suffocating purgatory, damper and more cloying than I had ever felt. Border patrolmen looked me over and quickly turned away, disappointed that I was a Gringo. I could feel no form or shape to the place, just heat, silence and chirping cicadas. I fought the urge to turn around and head back to California. Instead, out of stubbornness and ennui, I stayed.

On the way to Harlingen, we passed through the Continental Trailways bus depot in Laredo, where stocky Chicanos sporting shimmering Guayaberas hauled luggage and grapefruits beneath lacy mesquite trees, the bus’s back seats filled with peaceful Kikapoos, slant-faced Toltecs seemingly deposited far from their ancestral lands. I could sense and feel a literal decent into the landscape below me and a mysterious culture entirely unknown to me. I decided to relax and let the future reveal itself.

I quickly discovered that the band was filled with well-meaning amateurs, undisciplined and insecure, and inclined to default into the harmonic woodwork. A proper country band swings like a well-oiled gate, requiring a light rhythmic touch that sets dancers skipping across the floor. But I soon learned that Chicano and Anglo musicians possessed two very different senses of rhythmic feeling, and mysteriously, the resulting music that issued from us always seemed to simultaneously both accelerate and brake with the cumbersome gait of a three-legged horse. Sometimes the music sounded as though the band’s energy level diminished in direct proportion to the endless, deathly slow ballads the band leader would call out as the night unfurled, funereal in their solemnity, until I could imagine quarter-notes melting onto the floor, and all the musicians tipped forward, comatose, balanced on their noses like overturned statues. I could watch the three Chicano band members struggle to produce a simple, danceable beat, but it was not to be. I’d left behind a great thumping country band in Southern California, able to perform a wide array of musical styles. This mixed group had reduced its repertoire to a grab-bag of classic country tunes grown stale from repetition. But the band leader paid me every week, and if I complained, he’d raise my salary. There wasn’t much competition. The rest of the local musicians, losers to a man, served up a flat, monotonous mix of pop tunes drifted so far away from the original recorded versions that it sounded like the folk music of a drunken, newly discovered musical culture, and they seemed mainly preoccupied with impressing their girlfriends.

I took up residence in a concrete block cabin at the Poseiden Club in Harlingen, where the band had settled in for lengthy engagement, a scattering of cramped motel rooms crowded around a cocktail lounge. Ken, the man who managed the club was generous and friendly, and the rooms featured industrial-strength air conditioners, essential for surviving the summer heat there. But living at the Poseidon Club required constant interaction with both the staff and the customers, so after a short while I moved farther out Highway 77 and took up residence at the Tangelo Motor Hotel, owned and operated by a diminutive Mexican/Egyptian named Pedro Nasser, whose grandfather had emigrated to Mexico from Egypt in the Eighteenth century and spawned a large, garrulous family. Pedro’s relaxed presence greatly suited me, and besides being sweet-tempered and funny, he was a font of Rio Grande Valley lore. I learned to invent reasons to visit him in his office because something interesting was always happening around him, whether selling polyester Guayaberas from the trunk of his car or carving up an enormous fish, readied to be smoked and consumed. The back room of his office always smelled like fried potatoes twenty-four hours a day, which he would occasionally offer to me.

Most of Pedro’s tenants had rented rooms for several months at a time because they all worked for a utility company stringing electrical cables throughout the area, simple men, and friendly, always ready for a beer and a few good stories. The Rio Grande Valley was profoundly safe then, and no one locked their doors, and if you did, you were considered to be uppity. The motel itself was a simple collection of plastered two-story boxes decorated in a low-rent faux-Mission-style surrounded by stately date palms.

I continued to share my apartment with Kim. Somehow, if you lived in the valley you simply had a woman, and making that arrangement with Kim seemed to me as sterile as renting a lawn mower. I’d been watching her wait tables at the Poseidon Club, and took her home one night after a gig. Divorced at fifteen, she’d been raised in the Vieu Carre´ neighborhood of New Orleans, and after growing up in that nearly hallucinatory city, Harlingen bored her stiff. She’d been wandering from town to town and struggling to exist anywhere she could find someone willing to let her stay. In New Orleans, Kim’s drunken mother had hauled her from house to house like a suitcase, trying to escape the sinister black boyfriend who regularly beat her. By the time I met her she was trailing a string of broken relationships and surrendering herself to nearly any man who wanted her, simply trying to survive. For a few weeks I found it mildly thrilling to possess a young and willing girl to do my sexual bidding, but within a short time I became terribly bored with her, and I was never able to reignite much passion for her. She began squirreling away escape money and planning to return to New Orleans where, she claimed, she planned to visit her mother. She left a small cardboard box with me containing a few dresses, a pair of shoes, and a hair brush, and said she’d be back to retrieve them.

Within a few weeks after my arrival, a couple of local kids had captured a stray cat and poked out her left eye. Pedro held her down while I disinfected the socket. I named her Esperanza. Pedro would feed her while I was on the road, and upon my return I could hear her bouncing and bitching all the way upstairs to my apartment and, like any self-respecting cat, she’d immediately ignore me, throw herself down on my bed and bathe herself.

Since I lived a few miles out of town, I’d hitch-hike into Harlingen and buy groceries, which meant that I could purchase plenty of cheap, fatty beef or slip quickly past the vacuum-packed pork snouts and deteriorating head lettuce. The only reasonably exotic food to be had was in Chinese restaurants in Corpus Christi, ninety miles away, and all of the Mexican food in Harlingen tasted as though it all came from a single industrial-sized commissary. If I had a large load, I’d call a taxi driver in town. But no matter how much I wrangled with him, it always seemed to cost me more money to get home than it did to go into town. The Cabbie would cite a complex litany of state and local statutes, and I’d always wind up paying one fee for going into town, and a dollar more to get back to my apartment. But the good citizens of Harlingen didn’t seem to mind the inconvenience of receiving their Tuesday newspapers on Friday, or having to wait a week for a milk delivery because no one felt like going to the trouble of calling the local mini-mart and asking the clerk to call for a delivery.

The only entertainment available in town was to watch some of the local musicians perform on various nights. The Holiday Inn featured an aging couple named Fred and Nancy, moonlighting school teachers and dismally unenthusiastic musicians who where even more boring and uninspired than the band I already led. You could buy a T-shirt at a local mall that stated “Harlingen, Texas might not be the end of the world, but you can see it from here.” The only form of escape left to me was to resort to watching television, but there were only a few stations in the area, and they all shut down before midnight except for one forlorn channel broadcasting from Mexico, so I’d stay up late, drink beer and watch Star Trek on the single late-night Spanish-language station out of Matamoros. “Ola, Spok!”

I acquired a library card. Browsing through the stacks one day, and desperate for literary engagement, I discovered a trove of beat literature. Kerouac, Burroughs, Ginsberg, and a number of Evergreen magazines, deposited there by some mysterious hipsters I was never able to identify, and in rereading those powerful writers again I grew ashamed of my dissolution. Remembering the potent artistic friends and mentors I had left behind in Southern California, I could almost feel them lurking in the shadows and shaking their heads in disbelief.

I discovered that an old friend and his wife were living a half-hour away from me, and we got together occasionally, the three of us lost in an alcoholic fog that never seemed to subside. Occasionally I’d buy bus tickets for Kim and myself and we’d spend a few days visiting with them, but the joy we shared by re-acquainting ourselves always descended into a drunken rout, most of which I cannot remember. We devoted a lot energy to complaining about the Valley and its limited attractions, but after a few months they joined the Peace Corps and moved to Costa Rica and I was left to shift for myself. So, one afternoon I bought a six-pack of Jax beer, hopped a bus and took a day-long tour throughout the lower valley, and I began to discover it’s potent and feral beauty, ranch houses shimmering in the distance, seeming to hover over an endless sea of sugar cane, tall palms thrusting upward through the live oaks, and sunsets that silhouetted the flat horizon line against neon-red and blue clouds seemingly evaporating into infinity.

One morning, Ken picked me up at the Poseidon Club and drove me out to a small pistol range behind a taxidermy shop where we blasted away at paper targets with .357 magnum pistols while sipping whiskey out of large paper cups, Ken’s way of introducing me to an important aspect of Texan culture. To make him happy I dutifully blasted through a few boxes of shells and passed inspection.

Ken introduced me to Stan and Georgia, a couple who lived in a homebuilt log cabin several miles south of town. Stan was a master gunsmith and he and Georgia lived entirely without electricity, “off the grid” before I knew that anyone could live that way. Someone handed me a shotgun one morning and I found myself blasting away at white wing doves, none of which I managed to hit. And while I found the adventure to be exciting, I was disappointed to discover that once the birds had been shot, we cooked and ate only the breasts, tiny dots of dry flesh that struck me as tasteless. Later that night a couple of ominous men with sawed-off shot guns and automatic pistols dangling from their hips took Ken aside and conducted a hushed conversation with him. He looked ashen, and he would never reveal what the contents of that chat.

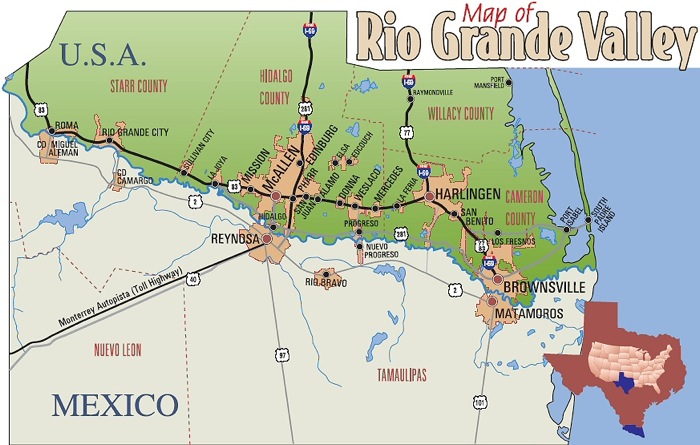

We toured throughout the Rio Grande Valley, Laredo, Corpus Christi, Raymondsville and Alice, grinding out country dance music in cavernous honky tonks, and working a long string of clubs that all seemed to be named “The Cowgirl.” By the mid-eighties, most country audiences had migrated toward popular music tinged with a country flavor, so between our sets disc jockeys funneled thumping disco into the clubs’ sound systems, all of it produced with considerably more polish than we were able to deploy. Mechanical bulls had invaded every dance hall, and we learned to focus on our playing while ersatz cowboys bounced on mechanical bulls in front of the bandstand as though they’d been flung from old-fashioned firemen’s nets. Drunk shrimpers wrestled each other for beers, and designer cowgirls, masked in pancake makeup and harsh red lipstick, silently cruised the men. None of them were real cowboys, just a bunch of youngsters caught up in the Urban Cowboy craze currently sweeping the country. But once in a while, the illegals, the silent, diminutive brown men with creased, sunburnt faces and wearing the short-brimmed straw hats of the working Vaquero, filtered into the club and silently absorbed our music, lost themselves in beer and homesickness, and then quietly slipped back across the border. The older Latinos preferred Conjunto, accordion-driven dance music played with gusto by the great masters Don Santiago Jimenez and Narcisso Martinez, much better musicians than us. Our musical palette of country standards and worn-out oldies paled in comparison.

The Rio Grande Valley is in fact a glorified flood plain, a howling sub-tropical desert unfurling itself along both sides of the river until it dissolves into the Gulf of Mexico. Nearly tropical, it is monotonous in its flatness, but surprising in the fall, when on certain afternoons, a buttery yellow light suffuses the atmosphere with a melancholy translucence that would haunt me throughout the entire year that I lived there. From the second-floor balcony of the Tangelo Motel, far beyond the edge of town, I sat in the shade of a banana tree, and watch restored World War Two bombers from the Confederate Air Force rehearse for an air show. A B-29 transformed into the Enola Gay bumped slowly overhead, improbably lost in a cloud of Jap Zeros and P-51 Mustangs.

For several centuries the Rio Grande Valley remained a Spanish military outpost, hidden from the rest of the country, but once the railroad came to Harlingen, real estate sharks set up shop. Land-hungry southerners flooded into the valley and bought huge chunks of it. Developers and lawyers quickly converted the barter system into a cash economy and the Tejanos found themselves lawyered off of their own land, threatened by Texas Rangers and assorted thugs who routinely ran them off at gun-point.

Imagine the Mexican border lifted up and set down a few miles within the United States, and sullen, gun-toting men with no last names who come here to bury the stink of unspeakable crimes. The bright green iguana dozes along the river banks, and wild peacocks, stupid and vainglorious, perch on barbed wire fences, shrieking like stuck pigs. Jaguar and coatamundi slither through shallow bar ditches. Fat, mustard-yellow crop-dusting planes dive-bomb the rippling cane fields. The shallow intercoastal waters boil with edgy, pissed-off sting rays.

In the mid-1800’s, Captain Richard King established a steamboat freight service that plied the Rio Grande until he discovered within himself the desire to assemble an enormously lucrative cattle ranching operation and a personal army staffed by Texas Rangers he’d hired to live on his ranch, furnishing them with the horses and guns they needed to do his bidding. Captain King was, in fact, a greedy, alcoholic thug given to running defenseless landowners off of their own property.

After the Civil War, King expanded his operations. Here, the quarter-horse and the Santa Gertrudis steer were born. The vaqueros came, along with the fences, the mesquite and the smugglers. Captain King’s good friend Robert E. Lee advised him to buy land and never sell it, so he assembled an enormous ranch staffed by an entire Mexican village that he’d transported to South Texas. Now there is King Ranch and a faint string of decaying towns, the whole mess crumpled and strewn along a searing, defeated coastal prairie. Four hundred years ago, shipwrecked Spaniards walked through here, and more followed. Yet the Valley could have been settled last year. Its amorphous borders, where Texas Rangers hung men from mesquite trees to extract confessions, have never been fully conquered.

Brownsville, the last and lowest border town, turns its back on Mexico. On the beach at Boca Chica, crude-oil seeps from the floor of Campeche bay and bales of wet marijuana wash ashore, all of it nesting gently on a pile of dead jelly fish, kelp, and a tossed salad of used pampers and beer bottles. It is silent there, except for the terns and the wind, and in the summer, the Gulf of Mexico turns as black as Pancho Villa’s heart. I said to myself, “You, my friend, are at the end of the world.” Indeed, the pirate Roche Braziliano once owned these waters, and took deep pleasure in capturing hapless Spanish soldiers and slowly spit-roasting them over a crackling fire.

So I hid, along with the other outcasts, serving my self-imposed sentence among the hit-men, the card sharks, the car salesmen and the smugglers. Everyone knew; don’t ask a man his last name. The locals filled the clubs, bought us drinks, and we kept our mouths shut. The cops, mostly young hot-heads or worn, middle-aged white men sporting sheriff’s bellies, were bored and mean, full of testosterone and frustration, wanting to escape the monotony of the Valley.

Aging divorcees gathered in these clubs, hungry for the attentions of any reasonably dressed man and willing to pay for it, wanting to show photos of their grand-children, and struggling to dull the sharp edges of old age and dried, loveless horror. Like the shit-birds that pick seeds out of cow dung, men lurked and waited for opportunities, and then routinely broke those women’s hearts.

All these multi-layered mysteries swirled together like the sand at the bottom of the gulf. up, down, north, south, truth, lies; all movable and mysterious. You could drift in and fade back out. No rules, no reason to do anything you didn’t want to, nothing to stop you. My life had become as porous as the Mexican border. There were moments when I looked at myself in the mirror, at my cracker-box apartment filled with stinking beer cans, the unending flatness of the coastal plains, the chubby Chicana girls who rolled their moon-struck eyes at me and reminded me too much of my Italian Catholic mother to screw, the whores in Reynosa, and it seemed as though the gods had thoroughly examined every aspect of my life, and pronounced the entire Valley and its inhabitants to be “Satisfactory.”

One day Kim was gone, back to New Orleans, as Captain Beefheart sang, “To get herself lost and found.” She left behind the cardboard box containing her blue cotton dress, a pair of leather sandals and a hairbrush, and she would call, again and again, and ask me to mail it to her. I always promised to do it, but I never did, and I asked Pedro to ship it for me. I could hear the fear in her voice. She was out there somewhere on the edge of some shaky, unstable world, struggling, and I knew she would come back if I asked. All I had to do was mail the package and make a phone call, but I didn’t, even though guilt weighed me down like a 50-pound sack of rice. I wanted her and I didn’t, so instead, I drank myself comatose and willed her into my past. I never saw her again.

I began to discover the great, secret beauty of this place. The shy Mexican girls who wrapped themselves in Catholic protection, the gulf breeze that burnished the shimmering, tropical greenery of the coastal flats, the charred and hungry smoke from roasting goats, all of these memories haunt me. My one-eyed cat used to cheerfully kill immense field rats and proudly present them to me at the front door, the moon bobbling above iridescent cantaloupe sunsets. But I found her dead one day, smashed flat by a truck, and it was time to leave.

I sat on the beach at Boca Chica and watched the horizon line between ocean and sky dissolve into night. Like the darkening sky, my time here was fading. Back in my room, I remembered the cocktail waitress in Victoria whose sinister boyfriend resembled Charles Manson, with her hundreds of makeup bottles and her death’s head smile, and the skinny coke-freak on the beach, begging me to stay. I shot some Polaroids of Pedro. The second cane crop of the season was up, and the banana trees were in full, oily flower. It was time to go back to California and its thug-filled country beer joints, railroad bums and hookers.

On South Padre Island, I collected small pieces of driftwood, shells, and rusty ship’s turnbuckles. Each glowed with the same soft, eerie yellow light of the south Texas seacoast. In my apartment, I would place them under a window and casually admire them. I brought them back with me to California. One day, I showed them to a friend. In the clear, high desert light, the wood, the shells, and the rusty metal bits were entirely unremarkable, no different than any piece of trash on the street. The yellow light didn’t travel with them, or with me. I threw them away and went out for a six-pack of beer.

One night just before I left the valley, the three Chicano musicians who struggled so unsuccessfully to produce a smooth rhythmic feel for our band suddenly appeared on my doorstep. “Get in the car and come with us,” said Arnold the drummer. I obeyed, and soon found myself sitting in a bar watching a pay-for-view presentation of the Ali-Holmes bout. After the slugfest ended, most of the audience simply left. But Arnold, Art and Rolando pulled back the stage curtains, revealing a drum kit, an electric guitar and a Fender bass. They began to sing and play beautifully, Romanticas, lush and expressive Mexican ballads filled with feeling, one song after the next, polished, and vibrating with artistic confidence. They simply didn’t want me to leave before I’d heard them play the music they knew and loved. After the corn-fed swill we’d been slogging through for the better part of the last year, I was stunned. “Get in the car,” said Arnold, smiling, and they drove me home.