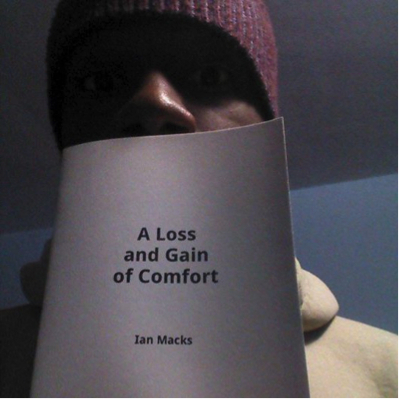

C.A. Mullins is the founder of Bottlecap Press, an indie publisher responsible for the release of some very interesting and beautiful chapbooks. One such chapbook is Ian Macks’ A Loss and Gain of Comfort, a work devoted to examining the space between being a good person for the sake of love and, in becoming a good person, failing to attain that love. Such instances of cosmic irony permeate the chapbook, creating an atmosphere of alienation and paranoia, where few moments of happiness exist. It’s an uncomfortable space to be in, but Macks’ effortless poems instill these feelings within the reader, thereby providing a deeply emotional experience. In the intriguingly introductory “Dr. Manhattan,” the identity of the graphic novel character from The Watchmen is assumed, thereby using analogy of isolation and Otherness to familiarize the reader with the daily mental experience of the chapbook’s persona. Just as Dr. Manhattan must experience profound separateness from other people, then so too does the chapbook’s persona experience alienation, which means his life’s emotional state paints the mood for the remainder of the chapbook.

C.A. Mullins is the founder of Bottlecap Press, an indie publisher responsible for the release of some very interesting and beautiful chapbooks. One such chapbook is Ian Macks’ A Loss and Gain of Comfort, a work devoted to examining the space between being a good person for the sake of love and, in becoming a good person, failing to attain that love. Such instances of cosmic irony permeate the chapbook, creating an atmosphere of alienation and paranoia, where few moments of happiness exist. It’s an uncomfortable space to be in, but Macks’ effortless poems instill these feelings within the reader, thereby providing a deeply emotional experience. In the intriguingly introductory “Dr. Manhattan,” the identity of the graphic novel character from The Watchmen is assumed, thereby using analogy of isolation and Otherness to familiarize the reader with the daily mental experience of the chapbook’s persona. Just as Dr. Manhattan must experience profound separateness from other people, then so too does the chapbook’s persona experience alienation, which means his life’s emotional state paints the mood for the remainder of the chapbook.

As far as mood is concerned, “Drunk Asshole” is a poem that runs right into that uncomfortable emotional territory. In this case: addiction, alcoholism, drinking for drinking’s sake, anger, disappointment, lovelorn and aching for companionship. To have to be fucked up in order to have sex is certainly not a good sign, but it is a part of the speaker’s journey, a part of his past. But the irony exists in the fact that, now having become a better person (i.e. no longer alcoholic), he is unable to confidently interact with members of the opposite sex. Here, then, is the overarching theme of A Loss and Gain of Comfort: Should one attempt to lead a better life, even if it means the result will not be conducive to easily finding love? There are, however slight, small glimmers of hope that there can be found someone to love. “Train,” for example, swells with the bigness of a heart filled with joy and happiness for someone to love, mainly from the fact that the speaker finds himself so calm and at-ease with this person. His being with her is such a natural thing, and really, in essence, is this not the goal of love? To feel so strongly good about someone else while with them that both are comfortable being together in public? As the persona of the poem says: “I never felt fake around you / This is real.”

In keeping with the chapbook’s themes, the aptly named “Contrasts” begins by meandering through the realm of unhappiness and progresses toward a better place, even if that place is not exactly happiness, per se. By the end of “Contrasts,” the poem has built itself up toward something like contentedness with an energetic surge of rhyme which, in this instance, functions quite well. This chapbook, like another chapbook available from Bottlecap Press, Trevor L. Sensor’s Manic Pixie Dream Poems, highlights the experience of big-hearted, romantic-minded insomniacs. This point of view is crystallized in Macks’ “Cradle,” which list-like concerns itself with the lonely occupations of solitude. But then, the alternative is plenty of free time to read and write instead of getting drunk and partaking in casual sex, which is a way of bettering one’s self. And herein lies the chapbook’s thematic conundrum again: if the persona reverted to his past ways of finding someone to love, then there would be no bettering of the self and there would be no writing; but if he focuses on bettering himself and writing, then finding love will be difficult and he will probably stay single. It is a difficult decision for anyone to make: whether to settle for easy and unhealthy relationships or to commit fully to working toward something healthier and more productive.

Stylistically, Macks employed little punctuation, which might be irksome, but then many of these poems read quite well as if they are to be performed (slam poetry, perhaps), in which case punctuation is of little to no importance. Those aspects which are important include Macks’ poetic messages, themes, and imagery, such as the strong sentiments expressed in “Touch,” which tightly compresses the person’s desires, anger, and frustration. Or consider the imagery of “Air Oceans,” a great poem of introspection and reflection. Well-written and well-worded, the idea of continuously drowning in the everyday air we breathe is beautiful; the implication being the ironic fate of Macks’ speaker who, though dying, must move forward, ever-continuously doomed to carry on a loveless existence. The remains of this realization are evident in “Hungover Heart” and “Bystander,” wherein the persona lays it all out on the line and is rejected, thereby made to feel like a stranger left behind, respectively.

A sort of existential nausea permeates Macks’ poetry, perhaps induced by the allusions to drinking, alcoholism, hangovers, and recovery, all of which is only heightened by the inability to find and maintain love with someone else. The pain of a lovelorn existence caused by seeking betterment of one’s self is continued in “If only for a second…,” wherein the speaker comes to this realization on his own. In observing the woman he loves, he sees what sort of person she is while in a relationship (i.e. the last guy she dated turns to alcoholic beverages for comfort now), but the persona still wonders what it would be like to be with her. This thematic development is continued in the chapbook’s concluding poems, “Didn’t” and “No Time.” The former provides an intriguing be-careful-what-you-wish-for twist while the chapbook’s closer astutely summarizes the chapbook’s thematic search; that is, which is the lesser of two evils: bettering yourself, even though it will mean being alone, or maintaining an unhealthy lifestyle so as to engage in unsatisfying relations with other people living similarly unhealthy lifestyles?

As noted above, it’s a difficult question to consider, which is why most people are comfortable sticking to their relationships, alcohol, or both, rather than take the time to fully ponder these issues. But Macks’ persona willingly travels through pains and pleasures in a devoted attempt to examine these questions. Ian Macks’ A Loss and Gain of Comfort beautifully conveys the dramatic irony of seeking self-betterment to attain someone, only to discover that in attaining betterment, all chances of being with that person have virtually vanished. Available from C.A. Mullins’ Bottlecap Press, Ian Macks’ heartfelt chapbook examines interesting territory and, for that, it is a clawing up-out of unhappiness and into some place better, even if it is solitary.

AUTHOR BIO:: dom schwab is a reader/writer of poetry/prose. dom is gay, GQ w/ no pronoun preference, a vegetarian, and lives in Chicago. dom’s most recent work has appeared in Zoomoozophone Review’s female/non-gender-conforming Issue 5, Boscombe Revolution Issue 3: Revolution & Gender, and JunkYard Kool, an anthology presented by Kool Kids Press.

AUTHOR BIO:: dom schwab is a reader/writer of poetry/prose. dom is gay, GQ w/ no pronoun preference, a vegetarian, and lives in Chicago. dom’s most recent work has appeared in Zoomoozophone Review’s female/non-gender-conforming Issue 5, Boscombe Revolution Issue 3: Revolution & Gender, and JunkYard Kool, an anthology presented by Kool Kids Press.