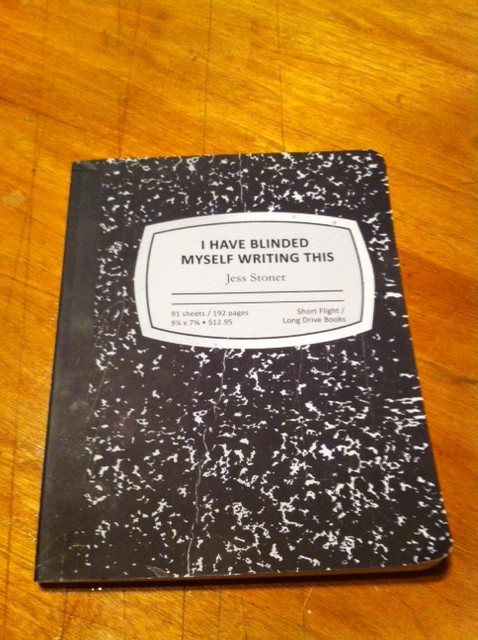

I HAVE BLINDED MYSELF WRITING THIS

Jess Stoner {lives here}

Short Flight / Long Drive Books, 2012

[1]

I am running late. I can’t find the bike pump. Bridget’s dad is helping me look. He can’t find it either.

I press on my front and back tires and decide I’ll bike to WHIP IN how it is: low on air.

I say, “Bye, Ron.”

He says, “You sure you have enough air?”

I have to peddle at least 2-3 times as hard because of my flat tires. People walking in a group state the obvious.

They say, “You need to put air in that.”

I make a point of looking back at them and nodding.

The messenger bag rubs against my skin. I think about the stuff I’m carrying and get happy.

I think, I’m going to meet Jess Stoner. I think, I’m going to get a copy of I HAVE BLINDED MYSELF WRITING THIS.

[2]

A person is sitting outside WHIP IN when I get there. I get off my bike and roll it into the outside seating area. My plan is to walk by this woman and lean my bike against something, giving me enough time to look at her, and her enough time to look at me.

Neither of us know each other. We’ve never met. Our meeting depends on our willingness to reveal ourselves.

I say, “Jess?”

She says, “Michael?”

We say, “Hey, nice to finally meet!”

[3]

My bike leans against the potted herbs behind me. My messenger bag is on the picnic table.

Jess keeps her bag on the space next to her on her side of the table.

Her book, I HAVE BLINDED MYSELF WRITING THIS, is on top of the table.

I say, “So there’s your book. Can I see it?”

She says, “Sure. It’s yours now.”

I study the cover and the spine and the back of the book. All of it resembles a composition book.

I open it and immediately realize there is no title page or copyright page.

Right in the middle of the first page:

THIS IS HOW IT BEGAN

I see illustrations and pictures and diagrams strewn throughout the book as I thumb through it. Some sentences are crossed out. Others bracketed.

Jess Stoner doesn’t use brackets like Blake Butler does in EVER. She uses brackets, both { } and [ ], to denote alternate speakers in dialogue.

I say, “I can’t wait to read it.”

She says, “I hope you don’t hate it.”

I say, “Here’s my book,” and I reach into my messenger bag.

She looks at the cover and says,

“Oh hey, I think I downloaded this for my Kindle recently. But I haven’t read it yet.”

I think, Neat.

We drink a couple beers and talk about small presses and indie writers. It’s fun, and we plan on meeting again.

[4]

The bike ride home is harder than the bike ride there.

Ron is reading MY ONLY WIFE on the balcony when I get home.

I say, “The woman I met at WHIP IN is friends with Jac Jemc, the woman who wrote MY ONLY WIFE.

Ron pulls on his cigar.

He says, “I really like this book.”

I pour a glass of water and sit on the papasan chair and start reading I HAVE BLINDED MYSELF WRITING THIS.

As I read, in the back of my brain I remember how Jess Stoner said she laid out the whole book in InDesign, as if writing weren’t arduous enough.

[5]

Her book is distilled prose. The premise is engaging.

I can’t stop thinking about what my life would be like if I lost a memory every time I injured my body.

It’s so psychosomatic.

What would my life be like if it took a memory to get my blood to coagulate and heal wounds?

A pinprick could result in forgetting I have a dog.

And what happens when I have no more memories to lose?

Jess Stoner’s premise is loaded with potential – the ultimate writing prompt – and what she does with it is brave.

[6]

I read,

… the tinted acne cream that never matched your winter tan.

And I think about how my acne cream never matched my winter tan.

At the illustration of the brain with the arrow pointing to the hippocampus, I touch a point above my temple.

I think, Could it be there?

I read,

This means the rest of your brain might not come to your aid even if it could. Soft, helpless tissue, waiting with breathless anticipation to see what will happen next.

I think, Something unsettling about not even your brain knowing what will happen next.

I read more.

I come to the crossed out sentences and don’t know what to make of them.

I think, Am I supposed to read the crossed out words?

I think, I’m not going to try.

But I still try.

I read about the amygdala, which is a special place in the brain:

Here is where you remember how to feel about what you remember.

I read,

We can’t be sure what we read is the truth, but if we stand before something made of stone, we believe it to be true. What then of something of paper? Could this, what I’ve written, be a statue of myself?

Because of its beauty I read this several times and still don’t quite know what to make of it.

Jess Stoner challenges me.

[7]

Because this book is a meditation on memories, and memories are mysterious – the way they are made, the way they pop up out of nowhere, the way they can change your mood for better or worse, the way they’re forgotten – it follows that this book works in mysterious ways, too. To keep things consistent.

At no point do I feel like I am master of this book, just like at no point will I ever be master of my memories. Nothing about this book is predictable.

There are parts of it I follow, and then I’m lost. I have trouble building a sense of accretion.

While this could be somewhat frustrating, the writing is so quiet and soft, like folds within folds, that any sense of disorientation soothingly drives home the premise of the book, namely, damnatio memoriae: the removal from remembrance.

Using sparse language and graceful spacing, leaving the majority of pages nearly blank, Jess Stoner makes me forget things I recently read, or not clearly remember other things, much like her narrator, except I don’t have to sustain an injury for this to happen, thankfully.

My Rating = ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()